Despite movements toward Health at Every Size (HAES), the truth of the matter is, size shaming is alive and well in this country. From the “Strong4Life” Georgia childhood obesity campaign to New York City’s “Cut your Portions, Cut your Risk” campaign scare tactics and body shame are part and parcel of the way we talk about health. And when actual bodies can’t be portrayed in ways that are framed as frightening enough, we create bodies to scare people. Case in point, the New York City “cut your portions” campaign apparently Photoshopped a man’s leg out of one ad – suggesting it was amputated from diabetes.

Although purportedly tackling size discrimination, the multi-part HBO series “The Weight of the Nation” is one of many voices still framing conversations about food and health as the “obesity epidemic.” In her essay, “Fat panic and the new morality,” which appears in a 2010 collection entitled Against Health, Kathleen LeBesco analyzes the “obesity epidemic” as a “moral panic.” In her words: “our insistence on turning efforts to achieve good health into a greater moral enterprise means that health also becomes a sharp political stick in which much harm is ultimately done.” Bodies of size – representing risk, ill-health, weak will, and loss of control — become an affront to the ‘American dream’ that anyone can achieve anything they put their minds to. Even the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently released a report suggesting that rather than focusing on individual willpower and control, the American medical establishment should concentrate efforts on making the environment less “obesogenic “ – for instance, through policies changing farm subsidies that preferentially support corn and soy growing over other fruits and vegetables. Yet, we continue individual level shaming and blaming – to disastrous ends, particularly among young women.

So how do novels aimed at teen audiences address issues of size? I have written before on the issue of YA novels and body image, and in that post I focused partially on Laurie Halsie Anderson’s novel Wintergirls (2009), which is written from the point of view of a young woman with severely disordered eating, and has caused great uproar among parents and educators. Such novels, which depict the self-loathing and torment of disordered eating, are potentially controversial in their handling of body acceptance. As I wrote then,

“Even the New York Times took up the issue, asking if such a novel—which explicitly discusses extreme exercise, binging, purging and caloric intake control, is potentially triggering young women already vulnerable to eating disorders? Can such novels be (mis)used as instruction manuals, yet another source of “thinspiration” for a community of young women already prowling pro-ana and other similar websites?”

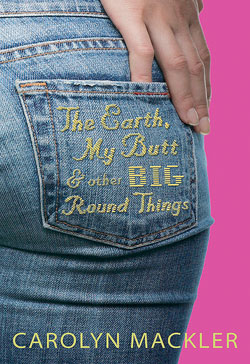

Yet, is there a way to portray both the anguish of size shaming in our culture and healthy body acceptance by a teenager without resorting to “preachy” lessons? Enter Carolyn Mackler’s Printz award-winning The Earth, My Butt, and Other Big Round Things (2003), which does just that (and gives a shout-out to the Adios, Barbie team besides!).

Fifteen-year old Virginia Shreves is the youngest child with a “larger-than-average” body in a thin, brilliant, seemingly perfect family. She’s started to fool around with Froggy Welsh the Fourth, and has gotten to second base, but knows better than to acknowledge their relationship in school, or push Froggy for a relationship due to the “Fat Girl Code of Conduct.” Mackler portrays Virginia’s size loathing with painful accuracy – her parents are far more concerned with her diet than her grades, she can’t face herself in a mirror, and shopping for clothes is a torture-fest.

But when Froggy seems to himself be pushing for a more public relationship, and then, her seemingly perfect older brother Byron is accused of a horrible crime against a female college classmate, Virginia is stumped. All the rules of her world seem to be turning themselves upside down. Virginia has to find her own power, making space for herself in her family, in her school, and in her own body.

The strength of Mackler’s novel is Virginia’s spot-on teenage voice. She deals with self-doubt, self-loathing, and even, yes, self-harm, but ultimately, she’s no victim. Virginia is smart, sassy, and strong – and she eventually finds inspiration within herself to love herself. But Mackler doesn’t stop there. She not only draws connections between size discrimination and self-harm, low self esteem or disordered eating, but she makes the connection between social expectations about women’s bodies and sexual violence.

Although Virginia’s family is the source of much size shaming, Mackler shows her protagonist finding and cultivating sources of adult and peer support. There is a fantastic teacher named Ms. Crowley who urges Virginia not to succumb to her parents’ problematic expectations, there is an equally fantastic dreadlocked doctor named “Dr. Love” who wants her to focus on health, not weight, and there’s a fantastic best friend named Shannon whose parents too seem to love Virginia for exactly who she is.

Mackler gives teen readers a potential roadmap for loving their bodies – Virginia gets a piercing, she calls her brother out on his anti-woman behavior, she finds a creative passion and follows it to form a webzine at school. Mackler even has Virginia’s teacher Ms. Crowley give her the book Body Outlaws (edited by the brilliant and talented editors at, yes, Adios, Barbie!). Mackler writes,

There are several pictures of women on the cover – all shapes and sizes and races – flexing their biceps, chowing down, flaunting tattoos.

“It’s a fantastic book,” Ms. Crowley says. “All essays by young women who are rebelling against body norms.”

… “Make sure to read the inscription,” Ms. Crowley adds…

I flip to the inside flap, where she’s written:

“I thought at last it was time to roll up the crumpled skin of the day, with its arguments and its impressions and its anger and its laughter, and cast it into the hedge.” – Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own.

I’ve never really gotten Virginia Woolf before, but this passage seems to make sense. It’s about throwing out old notions and reevaluating what you’ve always thought.

YA novels are a space that can portray both the problems of body shame and script some solutions. As Virginia eventually tells her loving, but size obsessed father, “…I have to tell you that I’d rather you don’t talk about my body. It’s just not yours to discuss.”

It’s not easy to portray both the journey through size loathing and light at the other side. Yet, Caroline Mackler’s novel does both with insight, intelligence, and laugh-out-loud humor. Certainly, it is one more vibrant voice in the body-loving revolution.

Related Content:

Size Activists Shed Light on Fat Shaming Campaign

Novel as Mirror: Teen Literature and Body Image

Are you an Ugly or a Pretty? Technology, Nature, and Beauty in Scott Westerfield’s “Uglies”

Body Outlaws: Rewriting the Rules of Beauty and Body Image

I’m going to have to check out this book. Body image is something that I feel needs to be addressed in YA books more regularly, because from my experience, it’s something that everyone deals with at that age, and frequently…the habits and beliefs we formulate as young adults regarding body image stay with us for the rest of our lives. Great post. I’m definitely a new follower now. 🙂

So glad you enjoyed it, Apri! Thanks for the comment!

Thanks for the book recommendation. I read it in two days! Enjoyed it. Please keep the recommendations coming!