A few weeks ago at my oldest son’s 8th grade graduation, I watched one 14-year-old girl after another walk awkwardly but determinedly across the school auditorium stage in skin-tight strapless mini-dresses and high stiletto heels. This was the first time that I’d seen these young teenage girls, many of whom I’d known for years, all dressed up. Sadly, I found it more disturbing than anything else. It really made wonder what the hell is going on with young American women today.

I don’t consider myself prudish, conservative, or old-fashioned. But I was taken aback to see that 99% of the girls had crammed their young bodies into super-tight and revealing outfits along with what a friend of mine used to call “fuck me pumps.” Most of them exuded an odd combination of pride in their grown-up, sexy outfits and discomfort with what it revealed and signified. Most were also struggling with the simple physical difficulty of walking around in stilettos and a short tight dress.

Corporatized Sexuality

When I had taken my son on a rare trip to a mall to shop for his graduation clothes, he told me that I had to check out the clothing company, Hollister. “It’s the worst, Mom,” he said. “You’ll see what I mean when you go in there.”

Walking through Hollister was an interesting prequel to the graduation ceremony itself. The store was structured to be a lavish, dim-light tunnel. It felt weirdly like a tubular shopping bordello. The brightest spots in the store were provided by huge, lit-up fashion photos of super-sexy young models in minimal clothing, which loomed down on shoppers like gods and goddesses from some strange new cult of adolescent body worship from the walls.

The girls’ section full of bikinis, short shorts, tube tops, and other super-skimpy summer wear, along with a few hoodies for that obligatory “street” vibe. Combined with the hyper-sexualized imagery and low lighting, it sent a clear message: Get sexy. And how? By buying these products and internalizing this imagery, of course.

To me, the store signaled that the marketing of pre-packaged, generic, corporatized sexuality to America’s youth has hit yet another new high (or more accurately, low). My son said that the clothing line is super-popular. He knew that I would hate it, and completely understood why. The difference between us was that while I was surprised by it, he understood that this is the new normal.

Bodily Fallout

I’m not a mother of girls, and don’t claim insight into how they understand today’s culture of early sexualization and bodily display. At 14, I was a post-hippie chick who favored ripped Levis and funky, loose-fitting shirts from the thrift store. It would never have crossed my mind for a split second to wear the sort of outfit that virtually all of the girls were wearing at this graduation. Like the one girl in a more modest dress who came from a recently immigrated Asian family, it wasn’t part of the culture I grew up with.

Neither were rampant eating disorders. Not long after attending the graduation ceremony, I went to another school-related function and fell into a conversation with a super-stressed mom who disclosed that her 12-year-old daughter was struggling with anorexia. She was doing her best to help her daughter as she juggled a job that required lots of travel and a husband whose work frequently took him overseas. But she admitted to feeling totally freaked, shocked, and distraught over her daughter’s disease. My stereotype of a mother whose 12-year-old daughter has anorexia is someone who’s obsessed with her weight and appearance, who’s constantly sending unconscious signals that a girl’s identity and self-worth rests on her dress size and beauty. But this woman didn’t strike me that way at all. Her body was at a comfortable, healthy weight, and she dressed in comfortable, casual clothes. Of course, I knew that I had no insight into the family dynamics behind the scenes. But there were certainly nothing on the surface that would suggest why this girl was afflicted with an eating disorder.

The woman said that she had been hearing about more and more young girls in the community who were cutting, anxious, anorexic, depressed. “I don’t know what’s going on,” she said. “I don’t understand why so many kids have these problems.” We talked about how life is much more stressful for kids today than it was when we were growing up. But there was also a reluctant recognition that a lot of kids seem to be caught up in currents of youth culture that we observe, but don’t really understand.

One thing that seems clear is that many girls and young women today are obsessed with their bodies in ways that are psychologically and spiritually unhealthy, and that this fixation is encouraged by advertising and mass media. To me, this seems incontrovertibly clear. It also seems like a social fact that’s extremely relevant to yoga.

Authenticity vs. Commodification

Now that yoga’s become so popular and mainstream, it occupies an important, but also vexed relationship to the body in North American culture. On the one hand, yoga offers an accessible means of learning how to connect to your own body as part of your authentic being. When practiced in a way that syncs body, mind, and breath while cultivating the intent of connecting to the deeper self, yoga can be a powerfully healing practice indeed.

Conversely, yoga can be practiced as a means of not only trying to sculpt the perfect body, but trying to construct the perfect persona. So, not only do you want to have zero percent body fat – you also want to be strong, flexible, and able to perform kickass asanas – and to be serene and happy, if not spiritually blissed out, pretty much all of the time.

This is fake. It reminds me of the 8th grade girls at graduation. Both share a well-intentioned, but misguided drive to mimic an external image that symbolizes reaching some wonderful state of internal self-actualization: Now you’re grown-up. Now you’re a yoga goddess. Now you’ve temporarily fooled yourself into believing that you’ve left all of the authentic messiness of who you really are behind.

It can’t and won’t work. Yet because we’re constantly being sold promises that it will – whether via Hollister or Lululemon – it’s hard not to internalize the hope that it might. Unfortunately, relating to our bodies as objects to be disciplined and displayed – whether as wannabe sexy teenagers or yoga goddesses – just feeds our cultural pathologies and further alienates us from ourselves.

What’s the Message?

The funny thing about yoga in this regard is that consistent practice will in fact naturally cultivate what our society considers to be a beautiful body. Of course, it won’t make everyone automatically “beautiful.” But given that lots of attractive young women are in the prime yoga demographic, it will move many in that direction. Which is wonderful. The conundrum, however, is that it opens the door to turning that beauty into a commodity.

In the yoga community as everywhere else. the body can be commodified to sell almost anything – classes, workshops, clothing, jewelry, books, DVDs jewelry, books, DVDs . . . and your self. Even more insidiously, we may relate to our bodies as “things” that must be made to look a certain way in order to give ourselves what seems like a solid anchor of meaning and self-worth. All-too-many girls and women measure their sense of personal value by their dress size, numbers on a scale, or approximation of some external ideal.

I think that it’s good for young women (and everyone else) to celebrate their beauty (and, when the time is ripe, sexuality) in authentic ways. But given the society we’re living in, I believe that this requires resisting some powerful cultural norms. For teen girls, it might mean rejecting the idea that you need to prove that you’re grown up by putting on an uncomfortable uniform of tight, short, low-cut dresses and high heels. For female yoga practitioners, it might mean countering the pre-packaged image of being serene, smiling, beautiful, bendy, thin, well-accessorized, and perfectly flawless.

At the risk of sounding preachy, I really think that the yoga community has the responsibility to think seriously about how we are representing beauty, the body, and the practice in our culture. Are the images being put forth ones that will encourage students to chase after yet another air-brushed image of commercialized beauty? Or do they somehow manage to signal that no matter how beautiful the body may be, the more meaningful beauty is always within?

Subverting the Beauty Paradigm

Happily, there are more and more images being produced that offer alternative visions of what yoga in this society might look and feel like. While I don’t want to hold anything up as the next ideal (which would undermine the project of encouraging new alternatives), I think it’s valuable to share and celebrate what we personally find interesting or inspiring.

So, here’s a few of my faves:

The above photos of Keri-Anne Telford, who teaches yoga at Exhale Venice and the Trapeze School of NY in L.A., were recently shot by Sarit Rogers of Sarit Photography (also in L.A.). I’m particularly psyched about Sarit’s new work as it’s going to be featured on the cover of a book on 21st Century Yoga that I’m co-editing with Roseanne Harvey.

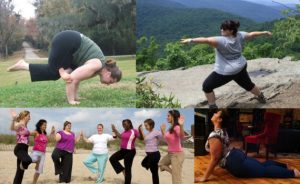

And this great collage of images courtesy of CurvyYoga.com:

Why strive to be a Barbie when being you is so much more creative, interesting, and authentically beautiful?

Originally posted at ThinkBodyElectric.com. Cross-posted with permission.

Related Posts:

“I’m Not a Size Zero. Can I Practice Yoga?”: Anna Guest-Jelley Says “Yes!”

One thought on “Subverting the Beauty Paradigm: Questioning the Relationship Between Body Image and Self Image, in Yoga & Beyond”