By Lisa Wade, PhD at Sociological Images

Earlier this year, Barbie posed for Sports Illustrated, triggering a round of eye-rolling and exasperation among those who care about the self-esteem and overall mental health of girls and women.

Barbie replied with the hashtag #unapologetic, arguing in an — I’m gonna guess, ghostwritten — essay that posing in the notoriously sexist swimsuit issue was her way of proving that girls could do anything they wanted to do. It was a bizarre appropriation of feminist logic alongside a skewering of a feminist strawwoman that went something along the lines of “don’t hate me ’cause I’m beautiful.”

Barbie is so often condemned as the problem and Mattel, perhaps tired of playing her endless defender, finally just went with: “How dare you judge her.” It was a bold and bizarre marketing move. The company had her embrace her villain persona, while simultaneously shaming the feminists who judged her. It gave us all a little bit of whiplash and I thought it quite obnoxious.

But then I came across Tiffany Gholar’s new illustrated book, The Doll Project. Gholar’s work suggests that perhaps we’ve been too quick to portray Barbie as simply a source of young women’s self-esteem issues and disordered eating. We imagine, after all, that she gleefully flaunts her physical perfection in the face of us lesser women. In this way, Mattel may be onto something; it isn’t just her appearance, but her seemingly endless confidence and, yes, failure to apologize, that sets us off.

But, maybe we’re wrong about Barbie?

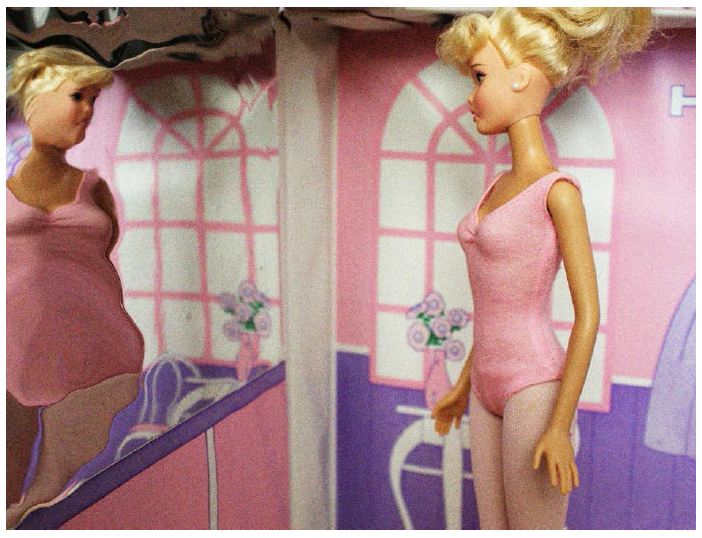

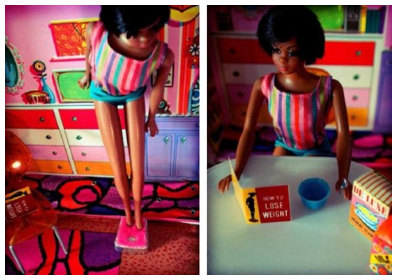

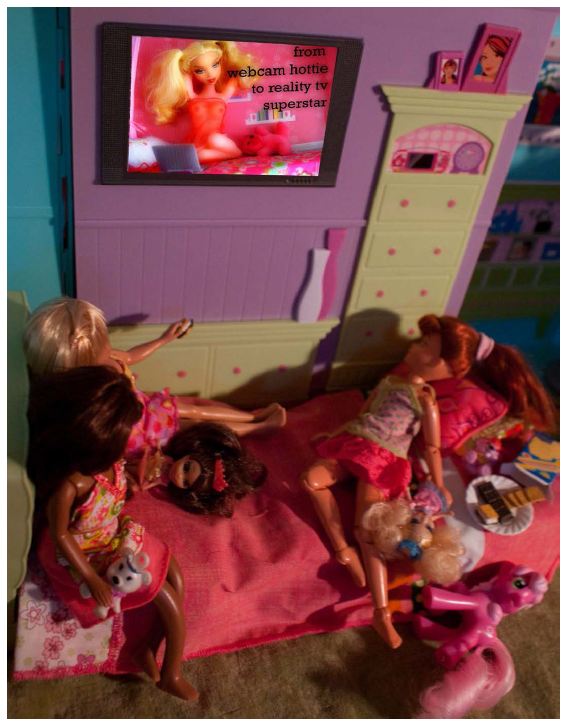

What if Barbie is just as insecure as the rest of us? This is the possibility explored in The Doll Project. Using a mini diet book and scale actually sold by Mattel in the 1960s, Gholar re-imagines fashion dolls as victims of the media imperative to be thin. What if Barbie is a victim, too?

Excerpted with permission:

Forgive me for joining Mattel and Gholar in personifying this doll, but I enjoyed thinking through this reimagining of Barbie. It reminded me that even those among us who are privileged to be able to conform to conventions of attractiveness are often suffering. Sometimes even the most “perfect” of us look in the mirror and see nothing but imperfection. We’re all in this together.

Originally posted at Sociological Images; cross-posted with permission.

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College and the co-author of Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

I liked the concept of humanizing Barbie, comparing her to the reality of the social pressures of a perfect body image. So many people are focused on attacking Barbie, putting her under a microscope in the same way we, as humans, put each other under a microscope (something we claim has very negative impacts on those being analyzed, i.e. drawing attention to flaws). If people are going to treat Barbie as if she were a real villainous diva, then she should also be considered an innocent victim to societal pressures that result in low self-esteem.

I have read many scholarly articles and studies regarding the strong power Barbie supposedly holds, however I played with Barbies as a kid and I loved all of them; I loved her purple car, stellar high-heels, and miniature sunglasses. Her body was the last thing I ever noticed. While this is anecdotal evidence at best, I think it’s still relevant. Everyone is different—that we can agree on—yet we treat each other the same.

At any rate, it’s good to know that there are new sources who study the other side of the Barbie coin! Thanks for the reference to The Doll Project!