Lydia X. Z. Brown is a queer, disabled, and east asian non-binary activist, advocate, writer, and law student. Brown, along with E. Ashkenazy and Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, have co-edited the first anthology of writing and artwork by autistic people of color, titled All the Weight of Our Dreams. We asked Lydia about the new book, the state of ableism, and what they look forward to for the future.

Vanessa Leigh for Adios Barbie (VL): You have described yourself as a “queer, disabled, and east asian.” How aware were you of your own multiple intersections growing up?

Lydia X. Z. Brown (LXZB): I didn’t necessarily use the language common in social justice spaces to describe myself when I was growing up, nor did I come to identify as queer until I ended up in college, but I was always aware that I was “different.” I didn’t really fit in with the white kids, but I clashed the most with the other east asian (and specifically the other Chinese American) kids in school. I thought it was funny to poke other people even though they clearly disliked it, and they started making the sign of the cross at me as if to ward off evil.

I was considered a girl, so I didn’t really fit in much with the boys past second or third grade. But I couldn’t fit in with either the girly-girl or tomboy type groups, because I was completely uninterested in pink and frilly but also hilariously unathletic on top of that. I wasn’t labeled as disabled either until eighth grade, but that quickly came with new complications—the school couldn’t conceptualize me as both gifted and disabled. (I’d been labeled “gifted” four years earlier in fourth grade, so was always thought of as the “smart kid” whether by people who liked or disliked me.) And I still didn’t fit in either with the not-disabled “smart” kids (was never the right kind of nerd) or the kids known as the “sped kids” (for “special education”). Other kids could find friends based on shared interests or hobbies, but relatively few people shared mine.

It’s impossible not to be aware of how strange and isolated you are in virtually every space you occupy when you’re always the weird kid. I remember constantly crying to my parents about how I had no friends, especially in school. When I did have friends, they were rarely in the same school as me (though it did happen) and often from other programs or activities. Friends were also often either much older or much younger than me, and in retrospect, almost all of my close friends were neurodivergent in some way or another, and many have since come out as queer or trans—very validating realizations. When in high school and college I learned from other autistic people that there were words to describe my experiences and the kind of person that I am, it was incredibly liberating.

VL: Your work and writing centers on how violence is perpetrated against disabled people with marginalized identities and experiences. Can you discuss the ways overt and not-so-overt violence occurs?

LXZB: Studies show that anywhere from 80 to 90% of women (and those lumped into the category of women) with developmental disabilities are raped at least once in their lifetimes. And over half of that number are raped at least ten times by the age of 18 (not counting what happens after turning 18). The number for people categorized as men is almost 40%. All of these numbers are likely severe underestimates, and also fail to account for race, gender identity/expression, and other statuses.

As much as 70% of all incarcerated people (who are disproportionately low-income, Black, Brown, and Indigenous) are disabled, and subject to further violence behind prison walls. Students most impacted by restraint, seclusion, aversives, and police intervention in schools are those who are both disabled and Black, Brown, and/or Indigenous. (Almost 90% of students at the Judge Rotenberg Center, a residential facility for people with disabilities notorious for using painful electric shock as punishment, are people of color, and over 80% are Black or Latinx. The two most well-known survivors, Jennifer Msumba and Andre McCollins, are both Black.) Disabled trans people face extremely heightened risks in medical discrimination that could be life-threatening. Over the past few decades alone, we know of over 400 disabled people murdered by family members and caregivers.

After police were called to confront Reginald “Neli” Latson, a Black autistic young man—basically for being Black in public—the subsequent altercation in 2010 resulted in him originally being sentenced to over 10 years for assault on a police officer, and he served almost two years in solitary confinement before he was finally released in 2015. After Steven Simpson, a white gay autistic man, was set on fire on his birthday in 2012 and later died from the severe burns covering most of his body, the killer received three to five years in prison, and the judge refused the prosecutor’s request to charge it as a hate crime. In 2013, a doctor in a Burlington, Vermont hospital suggested that well-known white, multiply disabled autistic activist Mel Baggs should consider refusing routine life-saving treatment, and when barraged with calls from the community, ultimately performed the procedure on hir functionally without anesthesia. Others, like Natasha McKenna, a Black psychiatrically disabled woman, die behind prison walls, or like Melissa Stoddard, a biracial autistic girl, die in their own backyards under the supposedly watchful eyes of Child Protective Services.

These overt acts of violence come part and parcel with smaller acts of violence, like being constantly disbelieved, literally talked over, spoken to in a baby voice, treated as though you’re scary for existing, expected to choose between one marginalized experience and another but not both, or constantly tokenized and expected to do everyone else’s emotional labor. All ableism is violence on our bodies/minds, and is part of a larger pattern of determining that some kinds of bodies and minds are valuable and worthy while others are not.

VL: You have been an advocate for an end to electric shock as punishment to disabled children and adults at the Judge Rotenberg Center (JRC) treatment facility outside of Boston. JRC is the last program in the country that is using electric shock “treatment.” The Food and Drug Administration proposed a ban on electric shock devices as used at the JRC in April. What is the status of the ban now? Is there anything readers can do to help at this point?

LXZB: The FDA is required by federal law to ask for public comments about any proposed regulations. Originally, comments were due by May 25, but the FDA unexpectedly extended the comment period, likely under pressure from the JRC and its supporters, so comments are now due on July 25. With any luck, the ban will go into force as intended, and all people currently receiving the shocks will be transitioned as quickly as possible (preferably immediately) onto treatment plans that do not rely on pain and fear.

Unfortunately, the JRC is hard at work doing anything they can to stop the ban from coming into effect. Its supporters are working overtime to convince the FDA and the public that a ban is a well-intentioned but misguided effort, that the shocks save people’s lives by inhibiting severe self-injury, that preventing people from receiving the shocks is depriving them of equal protection rights, and that the shocks are only minimally painful (“like a bee sting”). The reality is that across the country, people with disabilities can live successfully in the community and receive appropriate services and supports without use of painful, fear-based “treatment”—even when people have extreme self-harm or aggressive behavior. The reality is that the shocks, described by survivors as like an entire swarm of bees, have been documented to cause severe and long-lasting injuries, including burns, tissue damage, and seizures, not to mention heightened risk of anxiety, depression, suicidality, and post-traumatic stress. The reality is that the JRC’s argument boils down to this: If someone is hurting themselves or other people, we should inflict pain on them to get them to stop. JRC’s supporters continually twist the truth while pushing to maintain legal status of the torture it uses, all in the name of treatment.

The public has an opportunity from now through July 25 to send comments urging the FDA to do the right thing—disregard sensationalized anecdotes from the only program stubbornly clinging to electric skin shock, listen to the overwhelming evidence against the shocks in modern science, and move full speed ahead to ban inhumane, ineffective, and dangerous treatment. [Follow this link for more information and instructions, and for more information about leaving comments on the proposed ban.]

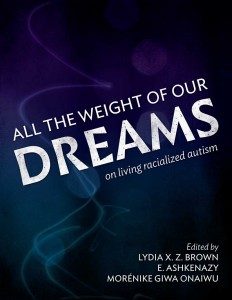

VL: All the Weight of Our Dreams: On Living Racialized Autism, an anthology of writing and artwork by autistic people of color, will be released this summer. You are the visionary and one of the lead editors of the project. How did the anthology come about?

LXZB: The vast majority of work put out by the autistic community and the broader neurodiversity movement is overwhelmingly white. This includes the founders of almost every autistic-led organization and the current leadership of most, as well as the majority of well-read blog posts and books coming from grassroots autistic activists. At most autistic events, it is rare to run into another autistic person of color, and it is problematic that a college-educated east asian with the last name “Brown” is often the only (or sometimes one of very few) person of color in an autistic-specific group or other disability event.

This constant unquestioned, unacknowledged erasure of autistic people of color, and public discourse about autism as essentially a “white people issue,” spurred me to instigate a new project—an anthology that would collect, uplift, and center the voices and experiences of those of us too often left out of the spaces that are supposedly for us. The anthology aims to serve two primary purposes: to raise public consciousness of our existence, politics, and art; and to offer some tangible evidence to others out there that they are not alone.

Set to be released over the summer, All the Weight of Our Dreams features both republished and new work from over 60 people, including children and elders, on topics ranging from mestiza identity to police violence, from disabled people’s movements to anti-Semitism, and from social anxiety to neurodivergent kinship. (We originally hoped the release would coincide with Autism Acceptance Day on April 2, but, ironically, ran into delays—proving that we really do run on Disabled Standard Time.) We are proud of our collective efforts, and excited about where we will go next! So far, in addition to the paperback and ebook set to come out soon, we plan to work next on producing an audiobook version that will feature at least some of the contributors reading their own work, as well as a Braille version.

I’m also personally excited to announce an Autistic People of Color Project aimed at collecting further funds to support autistic people of color in whatever endeavors might be useful—whether money for basic survival needs so often unavailable from other sources without paternalistic strings attached; scholarships to support education, internships, or conference attendance; or seed funding for new projects or campaigns. Right now, we have no money, but hopefully, that will change and the project will grow, providing one more concrete way for us to support one another.

VL: It seems as if mainstream media has only just begun to address ableism. What are some ways people might be unknowingly perpetuating ableism?

LXZB: Ordinary people participate in everyday ableism when they assume that adults with mental disabilities are basically like toddlers, when they pay for tickets to attractions like haunted insane asylums, when they repost memes about how inspiring or heart-warming or tear-jerking a disabled person is for existing in public, when they make offhand comments after mass shootings about bad mental health care systems, when they assume that conferences and other events are open to everyone but are actually inaccessible to many disabled people, when they insist on forcing their unwanted “help” on people with physical and sensory disabilities in public to get “good person” points, or when they casually refer to things they don’t like, understand, or want as “lame,” “crippled,” “insane,” or “crazy.”

VL: What do you think allyship around racialized ableism needs to look like to be impactful?

LXZB: Consider who you are inviting to write, speak on a panel, conduct a disability 101 training, or attend your event when trying to increase representation or inclusion of disabled people and disability issues. Are the sources all from white disabled people? Are the speakers white disabled people? If so, are you inadvertently pushing the idea that everyone is only allowed one “difference box,” or the idea that disability is ultimately a white people issue?

Be intentional in crafting your materials, website, events, or community speak-outs. If you don’t know anyone who is disabled and a person of color, ask the people who did come to mind—I promise they know someone, even if they have to think for a while before producing a few names.

It also means recognizing how you are advocating around disability issues. Are you focusing the majority of your time and attention on the accessibility of resort hotel pools, or are you directing your resources and social capital to issues like school pushout of disabled kids of color or mass incarceration of poor disabled people of color? If you’re pushing for police training on disability, are you also pushing for funding community-based organizations offering alternatives to policing, like peer-run mental health crisis teams? If you’re pushing for greater abortion access, are you using disabled people as a rhetorical tool (the idea that disabled people are scary, burdensome, or undesirable, and should be prevented from being born)?

Ask questions and start conversations. “Speak the truth even if your voice shakes.” Courageously decline invitations, or use your platform to enter the space and turn it over to those most impacted who otherwise wouldn’t have access to that space. Push back. Speak up and speak out. Work on educating the non-disabled people or white people in your life; we shouldn’t bear that burden of constantly educating everyone. Check in with us to see how we are doing.

Recognize that sometimes you just don’t know something, and sometimes there are genuine internal community conflicts over important questions that your input will do nothing to solve. Understand that we have multifaceted experiences with additional forms of oppression, and often, many forms of privilege. I’m also genderqueer and asexual, which compounds the oppression I already face as a disabled person of color, but I’m also college-educated and a U.S. citizen, which gives me immense amounts of privilege. I’m a person of color, but specifically, I’m a light-colored east asian, which means that right now, I should not be center stage in discussing racist police violence against Black people. Instead, it is my (and your, if you are not Black) responsibility to center the voices and perspectives of our Black peers, and particularly our multiply marginalized Black peers. As a start, read some Kiese Laymon, or Chanda Hsu Prescod-Weinstein, or Vilissa K. Thompson, or Leroy F. Moore, Jr., or Patricia Berne, or Sami Schalk.

VL: Where would you recommend our readers go to learn more about your work and the work of your colleagues?

LXZB: Definitely check out my blog or my portfolio of other goodies! For All the Weight of Our Dreams, see the official website.

I’d also strongly suggest looking up (and following, and supporting) the work of amazing multiply marginalized disabled and neurodivergent activists, advocates, attorneys, and scholars like Sonya Renee Taylor, Kay Ulanday Barrett, Haben Girma, Mia Mingus, Talila “TL” Lewis, Maysoon Zayid, Akemi Nishida, Eddie Ndopu, Dior Vargas, Karen Nakamura, Leah Lakshmi Peipzna-Samarasinha, Cyrée Jarelle Johnson, s.e. smith, Alice Wong, and of course my partner, Shain M. Neumeier.

These folks have all done (and are doing) so much incredible work, from producing the first documentary on Deaf in Prison with Al Jazeera to coordinating the People of Color and Mental Illness Photo Project, from developing groundbreaking work on trans and disabled intersections to creating the Disability Visibility Project, from fighting the Judge Rotenberg Center in the regulatory process to producing recorded performances of “verbal testimony of warriors, queer youth claimin’ the streets and the dance floor, mamaland tongue, and vulnerability.”

VL: You are completing your first year of law school, have edited an anthology, and are a full-time advocate and activist. How do you practice self-care to carry on with all of the work that you do?

LXZB: I’m bad at self-care. Most of us committed to this work are. We have a terrible habit of talking about the importance of self-care and then failing to actually practice it. I am working and trying to be better at this, though, because my physical and mental health are important to me, and if I run myself into the ground, there will be nothing left of me to keep doing the work. I make delicious food (love cooking!), talk with my partner until late at night, participate in intensive text-based roleplaying games, and sing along to entire albums of my favorite music. That is my self-care.

VL: What gives you hope for the future?

LXZB: The constant and changing nature of our movements. Getting better at recognizing the need for multifaceted strategies—that incrementalism for its own sake is a terrible way to do activism, but strategic incrementalism is sometimes necessary for individual people’s survival; that imagining and building the future we want to have is not just some pie-in-the-sky futile exercise, but vital if we are ever to achieve liberation outside existing systems. That as we burn out, we are also legion, and we are doing better with working to support one another—where one of us is unable to carry on, someone else can, that we are doing better about practicing (even if failing) at self-care, that we are actually valuing our bodies. That is disability justice.